Chapter 4

Union

union is a data structure that can store different types of data, but it can only store one type of data at a time. The size of union is the size of its largest data.

| |

Enumerations

| |

Enumarators are integer type, and can be converted to int, but not reversely.

| |

In practice, enumerations are used more often as a way of defining related symbolic constants than as a means of defining new types.

| |

Pointers

| |

array is the address of a 4-byte block of memory, &array is the address of a 12-byte block of memory.array + 1 adds 4 to the address value, &array + 1 adds 12 to the address value

A way to describe the type of variable is to remove the variable name, for example, short (*pas)[20], pas points to array of 20 shorts, the type of pas is short (*)[20]

sizeof(array_name) = size of the arraysizeof(pointer_name) = size of the pointer

| |

- Use

delete []if you usednew []to allocate an array. - Use

delete(no brackets) if you usednewto allocate a single entity.

Chapter 5: Loops and Relational Expressions

Prefix and Postfix increment

In prefix increment ++i, it increments the value and return the value. However, in postfix increment i++, it copys the value, increments the value, then returns the copy of the value.

For classes, the prefix version is more efficient than the postfix version.

Type Aliases

| |

It’s better to use typedef instead of #define. Consider the following:

| |

typedef approach doesn’t have that problem.

Chapter 7: Functions: C++’s Programming Modules

Pointers and const

| |

Assigning the address of a const variable to a pointer-to-const is valid, however, assigning to regular pointer is not.

| |

const doesn’t prevent changing the value of pt, it prevents changing the value which pt points to.

| |

If you want to prevent changing the value of pt, write DataType * const VariableName = &Data.

| |

finger and *ps are both const, and *finger and ps are not const.

Functions and Two-Dimensional Arrays

| |

data is an array with three elements. The first element is an array of four int values. Hence, the type of data is pointer-to-array-of-four-int, so an appropriate prototype would be:

| |

Now the sum function works with arrays with four columns.

| |

Pointers to Functions

Funcitons also have addresses. Pointers to functions are useful because we can pass in different functions in different times.

Here’s what a declaration of an appropriate pointer type looks like:

| |

We can use two ways to invoke a function with function pointers.

| |

Chapter 8: Adventures in Functions

Temporary Variables, Reference Arguments, and const

When the reference parameter is a const, the compiler generates a temporary variable when:

- The actual argument is the correct type but isn’t an lvalue

- The actual argument is of the wrong type, but can be conoverted to the corret type

lvalue is a data object that can be referenced by address, such as variables, array elements, stucture members. Non-lvalue include literal constants and expressions with multiple terms.

| |

Note that if refcude does not use constant references, c5, c6, c7 will show error. If there is no such rule, this will happen:

| |

In short, if the intent of a function with reference arguments is to modify variables passed as arguments, situations that create temporary variables thwart that purpose. Adding const means that we are not modifying them, so temporary variable cause no harm.

In C++11, there is a second kind of reference, called an rvalue reference. It’s declared using &&:

| |

The original reference type (&) is now called an lvalue reference.

Why Return a Reference?

| |

If square() returned int instead of int &, this could involve copying the entire structure to a temporary location and then copying that copy to y. But with a reference return value, x is copied directly to y, a more efficient approach.

Being Careful About What a Return Reference Refers To

Avoid these lines:

| |

It returns a reference to a temporary variable. The simplest way to avoid is to return a reference that was passed as an argument, like the square() function above.

Another way is to use new to create new storage.

| |

However, it is easy to forget to use delete later.

Function Overloading

| |

The function-matching process does discriminate between const and non-const variables.

| |

Function Templates

Let’s say we want to create swap() function that can swap two same type of data. One approach is to duplicate the function and overload it, however, it’s a waste of time and if we make changes to one function, we have to change every functions.

We can set up a swapping template like this:

| |

The template does not create any functions.Instead, it provides the compiler with directions about how to define a function. If you want a function to swap ints, then the compiler creates a function following the template pattern, substituting int for AnyType.

Overloaded Templates

If we want to create swap() function for C arrays, we can overload templates.

| |

Template Limitations

Let’s say we want to compare two numbers in a template, we can simply write things like a == b, however, the == equal sign (and >, <) is not defined under C arrays or other data structures. We must provide specialized template funcitons for particular types.

Explicit Specializations

Suppose we have a structure that looks like this:

| |

and we want to define a swap funciton for it, but only swapping salary and floor, then we can use explicit specializations. The prototype and definition for an explicit specialization should be preceded by template <> and should mention the specialized type by name.

| |

For a given function name, you can have a non template function,a template function,and an explicit specialization template function,along with overloaded versions of all of these. A specialization overrides the regular template,and a non template function overrides both.

Instantiations and Specializations

When the compiler uses the template to generate a funciton for a particular type, we call it instantiation of the template. If we write this:

| |

Then this is called implicit instantiation. The compiler creates a function Swap() for int type because the program uses Swap() with int parameters.

There is also explicit instantiation, which means that we can tell the compiler to generate a function for specific type for us.

| |

It basically tells the compiler “Use the Swap() template to generate a function definition for the int type.”

Note the difference between explicit instantiation and explicit specialization. The explicit specialization declaration has <> after the keyword template, whereas the explicit instantiation omits the <>.

| |

Explicit specialization tells the compiler “Don’t use the Swap() template to generate a function definition. Instead, use a separate, specialized function definition explicitly defined for the int type.”

Which Function Version Does the Compiler Pick?

The compiler will pick the function by such ranking:

- Exact match, with regular functions outranking templates

- Conversion by promotion (for example, the automatic conversions of char and short to int and of float to double)

- Conversion by standard conversion (for example, converting int to char or long to double)

- User-defined conversions, such as those defined in class declarations

For example,

| |

#4 and #7 are not viable. #1 is better than #2, since char-to-int is a promotion, whereas char-to-float is a standard conversion. #3, #5 and #6 are better than #1 since they are exact matches. #3 and #5 are better than #6 because #6 is a template. However, what happens if we have #3 and #5 at the same time? Most of the time, two exact matches are an error, however, special cases are exceptions to this rule.

Exact Matches and Best Matches

Suppose you have the following code:

| |

Pointers and references to non-const data are preferentially matched to non-const pointer and reference parameters. If only Functions #3 and #4 were available in the recycle() example, #3 would be chosen because ink wasn’t declared as const.

However, this discrimination between const and non-const applies just to data referred to by pointers and references. That is, if only #1 and #2 were available, you would get an ambiguity error.

If we have two template functions with exact matches, the more specialized is the better one. For example:

| |

The recycle(&ink) call matches Template #1, with Type interpreted as blot *.The recycle(&ink) function call also matches Template #2, this time with Type being ink. In Template #2, Type was already specialized as a pointer, hence it is “more specialized.”

Making Your Own Choices

| |

What’s That Type?

| |

What should the type for xpy be? We can use decltype keyworld as a solution.

| |

decltype should follow these rules:

If

expressionhas no additional parentheses, thenvaris the same type as the identifierIf

expressionis a funciton call, thenvaris the same type as the function return type. Note that there’s no need to actually call the funciton.decltypewith extra parentheses preserves references from the original expressionIf none of the preceding cases apply,

varis the same type asexpression

| |

Note that we can use typedef and decltype at the same time.

| |

Alternative Function Syntax

| |

What if the problem appears in return type? In this case, we cannot use decltype(x + y) for the return type, since parameters x and y have not been declared. The decltype has to come after the parameters are declared. Instead, we can write:

| |

Chapter 9: Memory Models and Namespaces

Separate Compilation

We can divide the program into three parts:

- A header file that contains the structure declarations and prototypes for functions that use those structures

- A source code file that contains the code for the structure-related functions

- A source code file that contains the code that calls the structure-related functions

However, this creates new problems. For example, if you had a function definition in a header file and two other files that are part of a single program included it, you would wind up with two definitions of the same function, which is an error.

Here are some things commonly found in header files:

- Function prototypes

- Symbolic constants defined using

#defineorconst - Structure declarations

- Class declarations

- Template declarations

- Inline functions

Here is an example of seperating a program into three files:

| |

Header File Management

You should include a header file just once in a file. It’s easy to include a header file multiple times accidentally. For example, you might use a header file that includes another header file.

We can use preprocessor #ifndef (if not defined) directive.

| |

The code above means “process the statements between the #ifndef and #endif only if the name COORDIN_H_ has not been defined previously by the preprocessor #define directive.”

Storage Duration, Scope, and Linkage

C++ uses four different schemes for storing data,

- Automatic storage duration: Variables declared inside a function definition (including function parameters) will be created when program enters a function or a block and freed when executuion leaves the function or block.

- Static storage duration: Varialbes defined outside function definition or with the keyword

statichave static storage duration. They persist for the entire time a program is running. - Thread storage duration: Variables declared with the

thread_localkeyword have storage that persists for as long as the containing thread lasts. - Dynamic storage duration: Memory allocated by the

newkeyword persists until it is freed with thedeleteoperator or until the program ends.

Scope and Linkage

Scope describes how widely visible a name is in a file. Linkage describes how a name can be shared in different units (files).

Static Duration Variables

| |

The static duration variables (global, one_file, count) persist when the program begins and execute until the program terminates.

Initializing Static Variables

All static duration variables have the following initialization feature: all its bits set to 0. It is also called zero-initialization.

| |

First, x, y, z and pi are zero-initialized. Then the compiler initialize y and z to 5 and 169. pi will be initialized until the atan() function is linked and the program executes.

Static Duration, External Linkage

| |

Static Duration, Internal Linkagek

| |

If we want to use the same variable name, we should addd static keyword.

| |

Static Storage Duration, No Linkage

| |

The difference between static internal linkage and static local variable is

- The name is only accessible within the function, and has no linkage

- It is initialised the first time execution reaches the definition, not necessarily during the program’s initialisation phases

More About const

Whereas a global variable has external linkage by default,a const global variable has internal linkage by default.

If, for some reason, you want to make a constant have external linkage, you can use the extern keyword to override the default internal linkage.

Chapter 10: Objects and Classes

const Member Functions

Consider the following code:

| |

In Stock::show() function, we cannot guarantee that it will not modify the object. To solve the issue, we can add const at the end of the function when we declare or write definition for it.

| |

Chapter 11: Working with Classes

Operator Overloading

A common computing task is adding two arrays. We might write something like this:

| |

We can overload the + operator so that you can do this:

| |

For example, operator+() overloads the + operator and operator*() overloads the * operator. We can also write operator[]() to overload the [] operator, which is the array-indexing operator.

Let’s say we have a Time class, and we want to use + operator to add two Time objects. We can write the following code:

| |

Now we can simply write time1 + time2 instead of time1.add(time2), and it will be translated to time1.operator+(time2).

Introducing Friends

There are still some restrictions when overloading operators. For example, if we overload the * operator and write time1 * 2.5, it translates to time1.operator*(2). However, 2.5 * time1 does not correspond to a member function since 2.5 is not a Time object.

We can write a nonmember function Time operator*(double m, const Time &t) to resolve this, but it raises a new problem: nonmember functions cannot access private data in a class. There is a special category of nonmenber functions, called friends, that can access private members of a class.

Creating Friends

To create a friend function, we need to add friend keyword in the prefix of the declaration.

| |

The friend function is not a member function although it is in class declaration, but it has the same access rights as a member function.

The definition should like this:

| |

Now, the statement time2 = 2.5 * time1 translates to time2 = operator*(2.5, time1)

Actually, we can write it as a non-friend function. However, it is better to write it as a friend function, since it ties the function and the class interface together, and allows potential access to private data in the future.

| |

Overloading the << Operator

Suppose trip is a Time object. To display Time values, we need to write trip.show() to print out the values. However, we could overload the << operator and make cout << trip print out the values.

We can overload the operator this way:

| |

How about a more complex one, something like this: cout << "Trip time: " << trip << "\n";

Actually, cout is an ostream object, and the ostream class returns a reference to an ostream object when implementing the << operator.

We just need to make operator<<() return a ostream object.

| |

A Vector Class

Automatic Conversions and Type Casts for Classes

C++ provides the following type conversions for classes:

- A class constructor that has but a single argument serves as an instruction for converting a value of the argument type to the class type.

For example, if we have a constructor Stonewt(double lbs) for Stonewt class. Then Stonewt myCat = 19.6 will convert 19.6 to a Stonewt object.

However, using explicit in the constructor declaration eliminates implicit conversions and allows only explicit conversions.

| |

- A special class member operator function called a conversion function serves as an instruction for converting a class object to some other type. This conversion function is invoked automatically when you assign a class object to a variable of that type or use the type cast operator to that type.

| |

Conversions and Friends

| |

Chapter 12: Classes and Dynamic Memory Allocation

A Review Example and Static Class Members

Let’s take a look at a class example:

| |

Notice that we initializes the static num_strings member to 0 in the .cpp file instead of the header file. That’s because we cannot initialize a static member variable inside the class declaration. Declaration only tells how to allocate the memory, but it doesn’t allocate memory. For static members, we need to initialize outside the class declaration (but not const static).

The StringBad class seems fine, however, there’s actually some problems. Let’s look at an example:

| |

When we pass by value, the function will create a temporary StringBad object that points to the same address as the headline does. After the callme function, the destructor will be called, causing the pointer to be released, which messes up the original string.

Special Member Functions

The problems with the StringBad class stem from special member functions. C++ provides the following member functions:

- A default constructor if you define no constructors

- A default destructor if you don’t define one

- A copy constructor if you don’t define one

- An assignment operator if you don’t define one

- An address operator if you don’t define one

Default Constructor

If we omit any constructors, the compiler will call the default constructor. If we define a constructor with no arguments, or its arguments have default values, it will become the default constructor.

However, we can have only one default constructor; otherwise, there will be ambiguity.

| |

Copy Constructor

A copy constructor for a class normally has this prototype: Class_name(const Class_name &);. The default copy constructor performs a member-by-member copy of the nonstatic members. Each member is copied by value.

A copy constructor is invoked whenever a new object is created and initialized to an existing object of the same kind.

| |

The middle two declarations may use a copy constructor directly to create metoo and also, or they may use a copy constructor to generate temporary objects whose contents are then assigned to metoo and also.

Back to Stringbad: Where the Copy Constructor Goes Wrong

The callme function creates a temporary variable that invokes the copy constructor, and this variable points to the same address as our original object. We should provide a copy constructor for the StringBad class.

| |

Assignment Operator

Assignment Operator has the following prototype:Class_name & Class_name::operator=(const Class_name &);.

An overloaded assignment operator is used when you assign one object to another existing object:

| |

Like a copy constructor,an implicit implementation of an assignment operator performs a member-to-member copy.

Back to Stringbad: Where the Assignment Goes Wrong

We should also provide a assignment operator for the StringBad class. The implementation is similar to that of the copy constructor, but there are some differences:

- Use

delete []to free the old string - The function should protect against assigning an object to itself

- The function returns a reference to the invoking object

Here is the implementation:

| |

The New, Improved String Class

We still need a few functions to improve the String class, such as comparison members or bracket notation.

Here is an improved String class:

String class

For static class member functions, it can only use static data members, since it is not associated with a particular object.

We added String & String::operator=(const char * s) to improve efficiency. Consider the following code:

| |

The program will do the following steps:

- Use

String(const char *)constructor to construct a temporaryStringobject - Use

String & String::operator=(const String &)to copy the object toname - call

~String()destructor to delete the temporary object

Which is slower than copying the C string directly to the String object.

Looking Again at Placement new

Using placement new is different from using regular new to allocate memory for objects. If we want to destroy the object that was allocated by placement new, we must call the destructor explicitly to do so.

| |

We have to call the destructor instead of delete. The reason is that delete does two things:

- It calls the destructor of the object

- It attempts to free the memory where the object was located

However, when using the placement new, the memory location is provided by us, and therefore delete might not know how to correctly deallocate it, leading to undefined behavior.

Member Initializer List

Let’s say we have a class that looks like this:

| |

We want to assign qs to the qsize variable, however, const variable can only be initialized to a value, not assigned to a value.

Calling a constructor creates an object before the code within the brackets is executed. Thus, the constructor will first allocate space for the four member variables, then enter the brackets and assign values into allocated space.

We can use member initializer list syntax to initialize member variables.

| |

Only constructors can use this initializer-list syntax. We also have to use it for class members that are declared as references.

In-class initialization is equivalent to using a member initialization list in the constructors:

| |

The items are initialized in the order which they are decalred, not in the order in which they appear in the initializer list.

Chapter 13: Class Inheritance

Beginning with a Simple Base Class

| |

Now we can create RatedPlayer class that derives from the TableTennesPlayer base class:

| |

With public derivation, the public members of the base class become public members of the derived class. The private portions of a base class become part of the derived class, but they can be accessed only through public and protected methods of the base class.

Constructors

When a program constructs a derived-class object, it first constructs the base-class object. We must use member initailizer list syntax to construct base-class object before we enter the body of the derived-class constructor.

| |

We we omit calling a base-class constructor, the program uses the default constructor.

| |

Special Relationships Between Derived and Base Classes

A base-class pointer can point to a derivedclass object without an explicit type cast and that a base-class reference can refer to a derived-class object without an explicit type cast.

| |

However,a base-class pointer or reference can invoke just base-class methods, not derived-class methods.

Polymorphic Public Inheritance

virtual determines which method is used if the method is invoked by a reference or a pointer instead of by an object. If you don’t use the keyword virtual, the program chooses a method based on the reference type or pointer type.

For example, if we have a base-class Brass and a derived-class BrassPlus, and a virtual function ViewAcct() for both classes.

| |

If we don’t have virtual keyword for the function, the reference will use Brass::ViewAcct() in both line of code.

When a method is declared virtual in a base

class, it is automatically virtual in the derived class, but it is a good idea to document which functions are virtual by using the keyword virtual in the derived class declarations.

The Need for Virtual Destructors

It’s also the usual practice to declare a virtual destructor for the base class. It ensures that the correct sequence of destructors is called.

| |

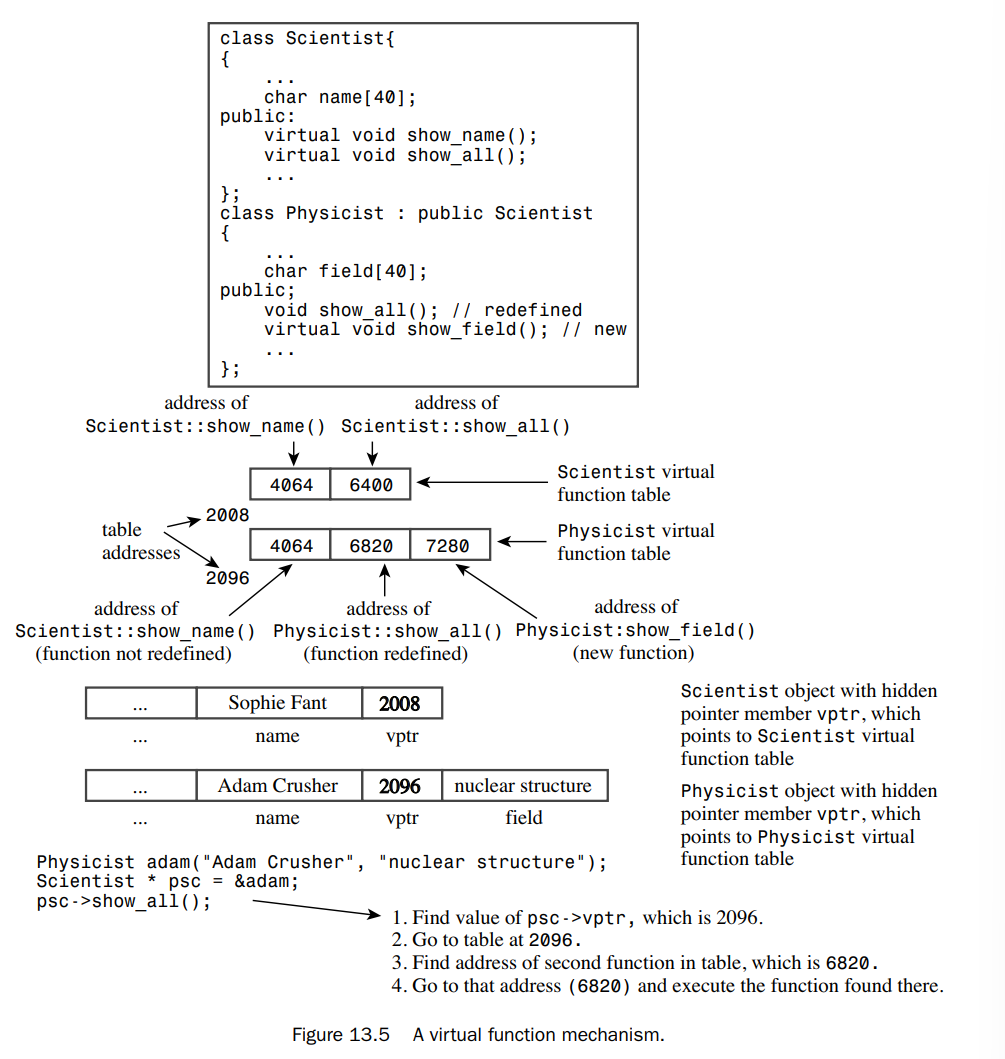

How Virtual Functions Work

The usual way compilers handle virtual functions is to add a hidden member to each object.The hidden member holds a pointer to an array of function addresses. Such an array is usually termed a virtual function table (vtbl). When we call a virtual function, the program looks at the vtbl address stored in an object and goes to the corresponding table of function addresses.

In short, using virtual functions has the following modest costs in memory and execution speed:

- Each object has its size increased by the amount needed to hold an address

- For each class, the compiler creates a table (an array) of addresses of virtual functions

- For each function call, there’s an extra step of going to a table to look up an address

Redefinition Hides Methods

Suppose we create something like the following:

| |

The new showperks() function that takes no arguments will hide the base class version that takes an int argument (it actually hides all base-class methods of the same name), instead of overloading the function.

If the base class declaration is overloaded, we need to redefine all the base-class version in the derived class.

| |

If we redefine just one version, the other two become hidden and cannot be used by objects of the derived class.

Access Control: protected

The protected keyword is like private in outside world and public for derived class. It’s useful for derived class to access to internal functions that are not available publicly.

Abstract Base Classes (ABC)

Suppose we want to create two classes, Circle and Ellipse. Of course we can first write the Ellipse class and then write the Circle class by inheriting the Ellipse class, since a circle is-a ellipse. However, this derivation is awkward, because circle is simpler than ellipse. It seems simpler to define a Circle class without using inheritance.

The useful thing about ABC is that we can extract the same part of circle and ellipse, and derive the Circle and Ellipse classes from the ABC. For the different part of circle and ellipse, we can create pure virtual functions in ABC and let derived class to override them.

When a class contains a pure virtual function, we can’t create an object of that class. C++ allows even a pure virtual funciton to have a definition. We can make the prototype virtual but still provide a definition in the implementation file.

Inheritance and Dynamic Memory Allocation

When both the base class and the derived class use dynamic memory allocation, the derived-class destructor, copy constructor,and assignment operator all must use their base-class counterparts to handle the base-class component.

For a destructor, it is done automatically.

| |

For a copy constructor, it is accomplished by invoking the base-class copy constructor in the member initialization list, or else the default constructor is invoked automatically.

| |

For the assignment operator, it is accomplished by using the scope-resolution operator in an explicit call of the base-class assignment operator.

| |

Chapter 14: Reusing Code in C++

Private Inheritance

We use public inheritance to create is-a relationship, however, when we use private inheritance, it creates has-a relationship.

It seems weird to use a private inheritance, since we have no right to access base class methods in the outside world, but actually, the derived class contains all the members and data of the base class, so it creates has-a relationship.

Student Class Example

Let’s say we want to create a Student class, the class should contain a string member and a valarray member. We could use containment to do so, but try private inheritance in here.

| |

We don’t need to create private data in the Student class, it’s because the two inherited base class already provide all the needed data members.

Initializing Base-Class Components

| |

Accessing Base-Class Methods

Containment adds an object to a class as a named member object, and we use the variable name as a interface to access the class. Private inheritance provides the same feature as containment, but only without the interface, however, inheritance lets you use the class name and the scope-resolution operator to invoke base-class methods:

| |

Accessing Base-Class Objects

The way to access base-class objects is to use a type cast. Because Student is derived from a string, it’s possible to type cast a Student object to a string object.

| |

Accessing Base-Class Friends

We use explicit type cast to invoke the correct functions. This is basically the same technique used to access a base-class object in a class method.

| |

<< (const String &) stu converts stu to a string object, then invokes the operator<<(ostream &, const string &) function.

The revised Student class

Containment or Private Inheritance?

Both containment and private inheritance can create has-a relationship, but which one should we use? In general, we should use containment to model a has-a relationship, and use private inheritance if the new class needs to access protected members in the original class or if it needs to redefine virtual functions.

Protected Inheritance

With protected inheritance, public and protected members of a base class become protected members of the derived class. The main difference between private and protected inheritance is when we derive another class from a derived class.

Redefining Access with using

Suppose we want to make a particular base-class method available publicly in the derived class. A easy way is to define a derived-class method that uses the base-class method. For example:

| |

Another way is to use a using declaration. For example:

| |

The using declaration makes the valarray<double>::min() and valarray<double>::max() methods available as if they were public Student methods.

Multiple Inheritance

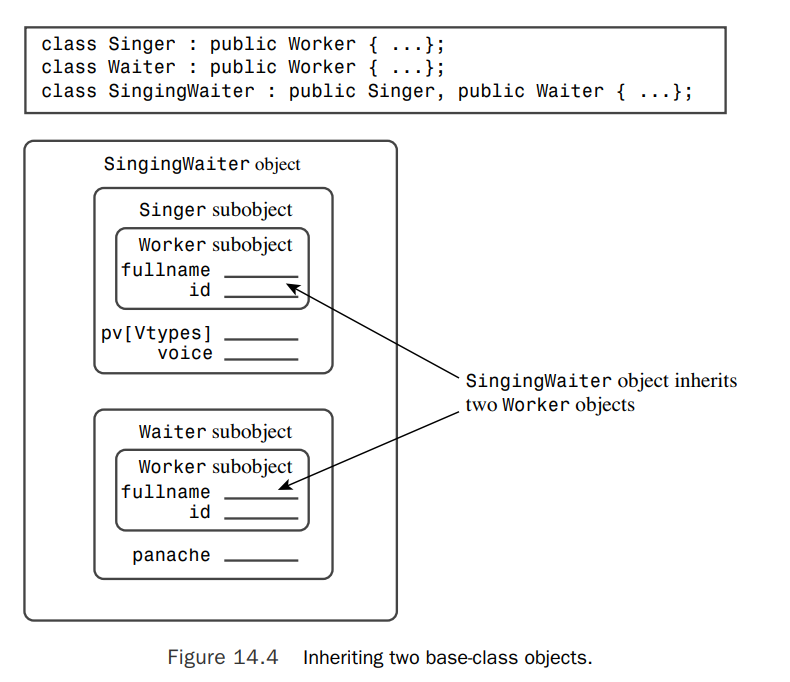

Let’s say we have a base class called Worker, and two derived class, Singer and Waiter. We can derive a SingingWaiter class from Singer and Waiter class:

| |

This is called multiple inheritance (MI).

MI can cause new problems.

- inheriting different methods with the same name from two different base classes

- inheriting nultiple instances of a class via two or more related immediate base class (

SingingWaiterclass encounters)

Let’s look at an example.

The main difference between Singer and Worker class is the Show function. What will happen if we call the Show function in SingingWaiter class?

How Many Workers?

SingingWaiter winds up two Worker components.

We can assign the address of a derived-class object to a base-class pointer, however, this does not work in MI, since it’s ambiguous now. We should specify which Worker we are pointing at:

| |

Virtual Base Classes

Virtual base classes allow an object derived from multiple bases that themselves share a common base to inherit just one object of that shared base class.

We would make Worker a virtual base class to Singer and Waiter by using the keyword

virtual in the class declarations:

| |

New Constructor Rules

C++ disables the automatic passing of information through an intermediate class to a base class if the base class is virtual. We have to call the virtual base class constructor explicitly.

| |

Which Method?

Use scope-resolution operator to clarify which funciton we want to invoke.

| |

A better way is to redefine Show() for SingingWaiter and specify which Show() to use (or use both).

However, the Show() function is an increment approach.

| |

We can’t combine Waiter::Show() and Singer::Show() without calling Worker::Show() twice.

We can use a modular approach to solve this. That is, providing a method that displays only the new components.

| |

Mixed Virtual and Nonvirtual Bases

Suppose, for example, that class B is a virtual base class to classes C and D and a nonvirtual base class to classes X and Y. Furthermore, suppose class M is derived from C, D, X, and Y. In this case, class M contains one class B subobject for all the virtually derived ancestors (that is, classes C and D) and a separate class B subobject for each nonvirtual ancestor (that is, classes X and Y). So, all told, it would contain three class B subobjects.

Virtual Base Classes and Dominance

With nonvirtual base classes, if a class inherits two or more members (data or methods) with the same name from different classes, using that name without qualifying it with a class name is ambiguous. If virtual base classes are involved, however, such a use may or may not be ambiguous. In this case, if one name dominates all others, it can be used unambiguously without a qualifier.

| |

The q() from class C dominates the definition in class B, thus, methods in F can use q() to denote C::q(). Neither definition of omg() dominates the other, therefore, we must add qualifier.

The virtual ambiguity rules pay no attention to access rules. That is, even if E::omg() is private, using omg() is ambiguous. Even if C::q() is private, q() would still refer to inaccessible C::q().

Class Templates

Let’s just see a template example.

| |

Notice that we have to put class declaration and definition in the same file, since class templates are not class, they are just instructions to the compiler about how to generate class (same as funciton templates).

An Array Template Example and Non-Type Arguments

Let’s begin with a simple array template that lets you specify an array size. One is to use a dynamic array and a constructor argument to provide the number of elements.

| |

Another approach is to use a template argument to provide the number of elements. This is what std::array does.

| |

T is a type parameter, or type argument. n is called a non-type, or expression argument.

Expression arguments can be an integer type, an enumerration type, a reference, or a pointer. Also the template code can’t alter the value of the arument or take its address. Also when instantiating a template, the expression argument should be a constant expression.

The constructor approach (the Stack example) uses heap memory, whereas the expressoin argument approach uses memory stack. This provides faster execution time, particularly if we have a lot of small arrays.

However, the drawback is that different array sizes generate different templates. Also, the constructor approach is more versatile, since you can resize the array.

Template Versatility

Using More Than One Type Parameter

We can also write this:

| |

Default Type Template Parameters

| |

Template Specializations

It is similar to function templates.

Implicit Instantiations

The compiler doesn’t generate an implicit instantiation of the class until it needs an object:

| |

Explicit Instantiations

| |

The compiler generates the class definition, including method definitions, even though no object of the class has yet been created or mentioned.

Explicit Specializations

Tells the compiler to generate the template in a particular way.

Let’s say we have a template, and we want to specialize it when the type is const char *:

| |

Partial Specializations

| |

Member Templates

A template can be a member of a structure, class, or template class.

| |

We can also write the definition outside the class template, but it depends on the compiler. Some compilers don’t support.

| |

Templates As Parameters

We can write:

| |

Here template <typename T> class is the type, and Thing is the parameter. Suppose we have this declaration Crab<King> legs;. Then the template argument King must be a template class whose declaration look like this:

| |

For example:

| |

We can also mix template parameters with regular parameters.

| |

Template Classes and Friends

Template class declarations can have friends, too. There are three categories of templates’ friend:

- Non-template friends

- Bound template friends, meaning the type of the friend is determined by the type of the class when a class is instantiated

- Unbound template friends, meaning that all specializations of the friend are friends to each specialization of the class

Non-Template Friend Functions to Template Classes

| |

This declaration makes the counts() function a friend to all instantiations of the template. But the problem is, how do this function access a HasFriend object without having any parameter?

It could access a global object; it could access nonglobal objects by using a global pointer; it could create its own objects; and it could access static data members of a template class, which exist separately from an object.

What if we want to pass an object as a parameter? Can we write:

| |

The answer is no. The reason is that HasFriend is not a object. We need to indicate a specialization. For example:

| |

Notice that report() is not a template function; it just has a parameter that is a template. This means that you have to define explicit specializations for the friends you plan to use:

| |

Bound Template Friend Functions to Template Classes

We can make friend functions a template and bound them with each specialization.

First, declare each template function before the class definition.

| |

Then declare the templates as friends inside the function:

| |

In the report() function, we omit the template specialization in <> , since the argument can be deduced from the function argument.

The last thing is that we must provide template definitions for the friends.

| |

Unbound Template Friend Functions to Template Classes

The bound template friend functions in the preceding section are template specializations of a template declared outside a class. An int class specialization gets an int function specialization, and so on.

By declaring a template inside a class, you can create unbound friend functions for which every function specialization is a friend to every class specialization.

| |